Slow Art Day has asked its 2013-14 college interns to write short summaries of their own experiences looking slowly at artworks of their choosing. Jennifer Latshaw, Slow Art Day intern from De Paul University, writes here about her experience seeing the unexpected.

Looking at art slowly is not my typical way of visiting a museum. Like many others, I tend to quickly stroll through any special exhibits that are currently on display and then visit some old favorites without spending much time with any single work. As a result, when I visited the Art Institute of Chicago to complete my slow looking assignment, I decided to find a famous work that I had never really focused on before. While the impressionist collection is a highlight of the museum and a section I’ve visited many times before, I guessed that I could find a painting there that had only gotten the quick treatment from me before.

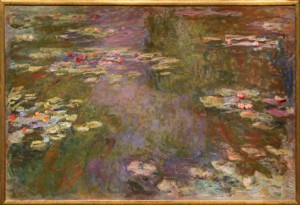

I chose one of the most popular and well-known paintings in the collection – Monet’s Water Lily Pond, 1917-1922. Of course, I’ve seen this painting before – so have many millions of people. It is such a familiar painting that I wondered if slow looking would reveal anything new.

I started the exercise by standing a few feet away from the painting in the gallery. Then after a few minutes I moved farther away. Eventually, I then got closer again. Not surprisingly, I saw different things depending on my distance from the painting. Up close the painting appeared to simply be smudges of color with no rhyme or reason to where they were placed. I noticed how it was thick in some places and sparse in others. I had not really noticed or thought about the thickness of the paint. Moving farther away from the painting, the larger image came into view. At my farthest from the canvas, I sat on a bench across the room and considered the entire painting at once. From this distance, the lilies appeared to be sitting on top of the lake with dramatic brush strokes of contrasting colors to the rest of the painting suggesting movement or reflection to give depth and dimension to the entire image.

Varying distance also allowed me to really reflect on the way the colors interact in the image. Up close I could see not just the relative thickness of the paints but also the individual pinks, reds, yellows, and purples. When viewed from farther away they came together to make greens and browns. I had never really taken the time before to see how colors change depending on perspective. It’s one thing to learn that in color theory class. It’s another thing to really experience it from a session of slow looking.

My original goal was to look for five minutes and then jot down some notes about the experience. Once I really started to look, however, I could not get enough of the painting. During the first minute or two, I glanced at my watch every 10 or seconds to see how long I had been looking. But after that, I found myself caring less about the time and caring more about seeing new things in the painting. And before I knew it, I had been absorbed in looking at Monet’s Water Lily Pond for 30 minutes.

One unexpected and surprising benefit was that slow looking is relaxing. By focusing on one painting I was able to stop multi-tasking and really pay attention. Everything else that would regularly consume my thoughts was gone and I was left only with Monet, his beautiful water lilies, and the ability to see so much more than I ever realized was there.

– Jennifer Latshaw, De Paul University

Claude Monet’s Water Lily Pond among other great works are available to view at the Art Institute of Chicago. The Art Institute of Chicago is not currently a 2014 Slow Art Day venue. Sign up to host here!