For years now we have been engaging in the art of slow looking. Slow Art Day is, in some ways, part of the Slow Movement, which seeks to reintroduce aspects of slowness. In many cases the “slow” values are ones that we have long lost, dating back to the introduction of mechanical time-keeping, which put time and its importance at the centre of our lives. Slow Art is but one of many other ‘slow’ activities; for example, the Slow Food movement thrives in many parts of the world. What I personally find intriguing, though, is the link between Slow Art and Slow Cinema, the subject of my on-going research. We published a brief blog entry about Slow Cinema before, which I want to expand on here.

The term ‘Slow Cinema’ was coined in 2004 by film critic Jonathan Romney. Since then it has been widely in use, although the term is somewhat limiting and derogative as ‘slow’ implies boredom for many people. The truth is that the aesthetics of Slow Cinema can be found as far back as the very beginning of cinema history, for example in long takes, which are (often mundane) events filmed in their entirety without a cut. Hungarian director Béla Tarr only cut when the reel came to an end, after about ten minutes. Lav Diaz from the Philippines, who used to be a painter but has now shifted to filmmaking, often goes as far as recording events without a single cut for as long as twenty minutes.

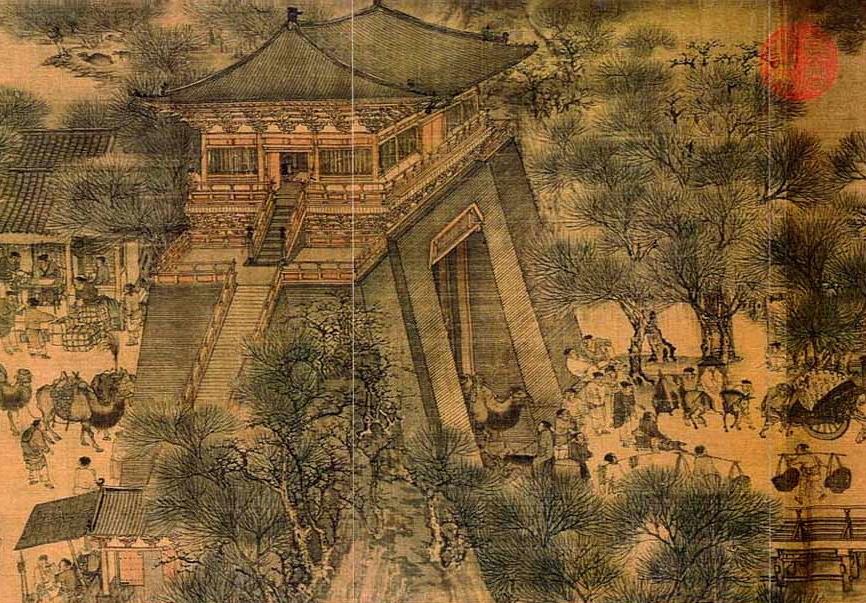

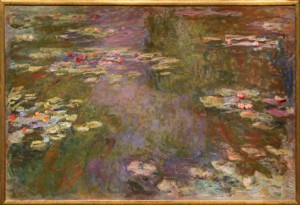

This, the use of an often static camera with little movement in the film frames, might remind one of paintings – only here these paintings are not hanging on a wall, but instead are projected onto a screen. The result, however, is the same. The viewer sits in front of the visual image, studying every detail of the frame, and may find him- or herself marveling at the beautiful rural landscapes that are often found in slow films. Take Michela Occhipinti’s Letters from the Desert (2012), set in rural India. The protagonists appear as mere dots in the landscape.

Still from Michela Occhipinti’s “Letters from the Desert”

Or take Catalan filmmaker Albert Serra’s Birdsong (2008), which is not only a comedic study of the Three Kings on their way to Bethlehem but also a stunning portrayal of empty landscapes.

Still from Albert Serra’s Birdsong

Then there is also Panahbarkhoda Rezaee from Iran, whose superb Daughter…Father…Daughter (2011) shows the audience a stunning Iranian landscape we perhaps never thought existed.

Still from Panahbarkhoda Rezaee’s “Daughter…Father…Daughter”

And there is Caspar David Friedrich’s famous Rückenfigur that appeared in Lav Diaz’s Death in the Land of Encantos (2007), an overwhelming nine-hour film set in the aftermath of a natural catastrophe that finds little likeness in the Philippines.

Caspar David Friedrich, and Lav Diaz’s “Death in the Land of Encantos”

There is more to the link between Slow Art and Slow Cinema than the apparent focus of traditions of landscape painting in the latter, however. For a long time I have thought and argued that slow films should be screened in galleries and museums. Locations govern our experiences; hence people tend to go to the movies to escape from reality, to see some action-laden blockbuster that puts them on a roller-coaster ride through the full spectrum of human emotions. A gallery audience has different expectations, ‘slower’ expectations, in fact, so that a projection of the fourteen-hour long Crude Oil (2008) by Wang Bing might sit much more at ease in this surrounding than it would in a cinema. And indeed, slow-film directors are more and more moving into gallery spaces, merging their work with other forms of art. Taiwan-based Tsai Ming-liang, whose superb short film Walker is available and free to see for everyone, even shot Visage (2009) in the Louvre after the museum commissioned him to do so. Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul, whose Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2011) won the Golden Palm at Cannes in 2011, is also widely known for his gallery works, such as Photophobia. His short film Dilbar is also available for you to watch online.

It is in this light, then, that I don’t see Slow Art and Slow Cinema as being separate from one other. As mentioned before, there are several slow activities thriving around the world. We have seen everything from Slow Education to Slow Finance to Slow Parenting. But none of these are so intricately intertwined as are Slow Art and Slow Cinema.

You can find more information, thoughts, film reviews, and interviews with directors on my website, The Art(s) of Slow Cinema. Or you can get in touch via theartsofslowcinema@gmail.com. I’m always happy to have slow discussions with people!

– Nadin